There are currently no adjuvant therapies recommended

after nephrectomy for patients with renal cell carcinoma

(RCC)

[1]. Drugs that target the vascular endothelial growth

factor receptor (VEGF-R) such as sunitinib and sorafenib are

effective in disease control in the metastatic setting;

however, they rarely completely eradicate the disease

[2] .A number of trials have investigated whether adjuvant

VEGF-targeted therapy can improve outcomes. To date,

results have been reported for two studies

[3,4]. The first

was a randomised phase 3 study (ASSURE) involving

1943 patients with completely resected RCC (pT1b–4 and

any N grade; Supplementary Table 1)

[4]. Patients were

randomised 1:1:1 to sunitinib, sorafenib, or placebo. The

disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) results

for sunitinib were hazard ratio (HR) 1.02 (97.5% confidence

interval [CI] 0.85–1.23) and HR 1.17 (97.5% CI 0.90–1.52),

respectively.

In the ASSURE study, 62% of patients in the sunitinib arm

developed grade 3 or 4 toxicity and 34–44% withdrew

(depending on the dosing cohort; Supplementary Table 1).

The sunitinib and sorafenib doses were modified during the

trial to address toxicity concerns. This did not appear to

affect efficacy in an exploratory subset analysis. There was

no survival advantage for either drug, with not even a trend

towards benefit in the treatment arm.

The S-TRAC trial was the second double-blind, placebo-

controlled, randomised phase 3 trial for which results were

reported

[3] .The results contradict ASSURE for DFS. The

S-TRAC study included 615 patients in a 1:1 randomisation.

The HR was 0.76 (95% CI 0.59–0.98;

p

= 0.03) for DFS, and OS

was immature. Grade 3/4 toxicity in the study was 60.5% for

patients receiving sunitinib, which translated into signifi-

cant differences in quality of life in terms of loss of appetite

and diarrhoea. The study was smaller than ASSURE and had

shorter follow-up. While the majority of patients over-

lapped, S-TRAC consisted of a population at slightly higher

risk. Furthermore, there was no central radiologic review in

ASSURE. This point is important because the DFS HRs, the

primary endpoint of the trials, were different (central

review for S-TRAC and investigator review for ASSURE,

Supplementary Table 1). It is noteworthy that the investi-

gator assessment for DFS in S-TRAC did not reach statistical

significance (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.64–1.02;

p

= 0.08), as was the

case with ASSURE.

These data prompt a number of questions that need to be

addressed before we can consider changing the standard of

care. First, is DFS a good surrogate endpoint in this setting?

OS takes longer to achieve, and DFS has at times translated

into an OS advantage in the adjuvant setting in other

diseases

[5–7]. In breast cancer trials, DFS HRs

>

0.76

without OS benefit have resulted in regulatory approval and

adoption as a standard of care

[6]. Therefore, DFS is a

reasonable endpoint and a precedent exists, but DFS needs

to translate into OS in the long run

[7]. The assumption that

this OS signal is inevitable with S-TRAC is questionable

owing to the preliminary OS results in ASSURE and S-TRAC

(HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.72–1.44;

p

= 0.94 for S-TRAC; HR 1.17,

97.5% CI 0.90–1.52;

p

= 0.1762 for ASSURE, Supplementary

Table 1). There are also uncertainties for the current

treatment algorithm for metastatic RCC. Treatment for

first-line metastatic renal cancer is VEGF-targeted therapy,

as is being tested in the adjuvant setting. Cross-resistance

between VEGF-targeted therapies occurs, and it is possible

that patients who relapse early on sunitinib will do less well

with subsequent VEGF-targeted therapy

[8] .This has been

described as ‘‘the law of diminishing returns’’ in VEGF-

resistant metastatic RCC

[9]. Currently there is no indication

of even a trend towards a survival advantage in either study,

although the data are immature. To achieve positive results

after initially overwhelming negative OS results to date,

much later analysis after longer follow-up will be required.

The results would need to show the Kaplan-Meier OS curves

parting significantly after a number of years of follow-up in

a nonproportional HR manner. It seems uncertain that this

will occur from the data available to us.

In reality, the definition of early metastatic disease is a

grey area. The presence of metastasis is determined via

cross-sectional imaging, which is only able to identify

sizeable cancer deposits from a molecular perspective.

Therefore, large numbers of patients with high-risk disease

probably have early, as yet undetected, metastatic disease.

Intervention with sunitinib in these patients will essentially

be treating early metastatic disease. Stabilisation with

sunitinib, especially at the beginning of the intervention

period, would therefore be expected. Perhaps a more

pertinent question is why this was not seen in ASSURE.

Nevertheless, the data available to us do not currently

support the hypothesis that VEGF-targeted therapy can

prevent relapse and extend survival.

What we can confidently say is that there is an issue

around tolerability, which was consistent in both studies. A

year of therapy clearly comes with significant toxicity that

can affect quality of life.

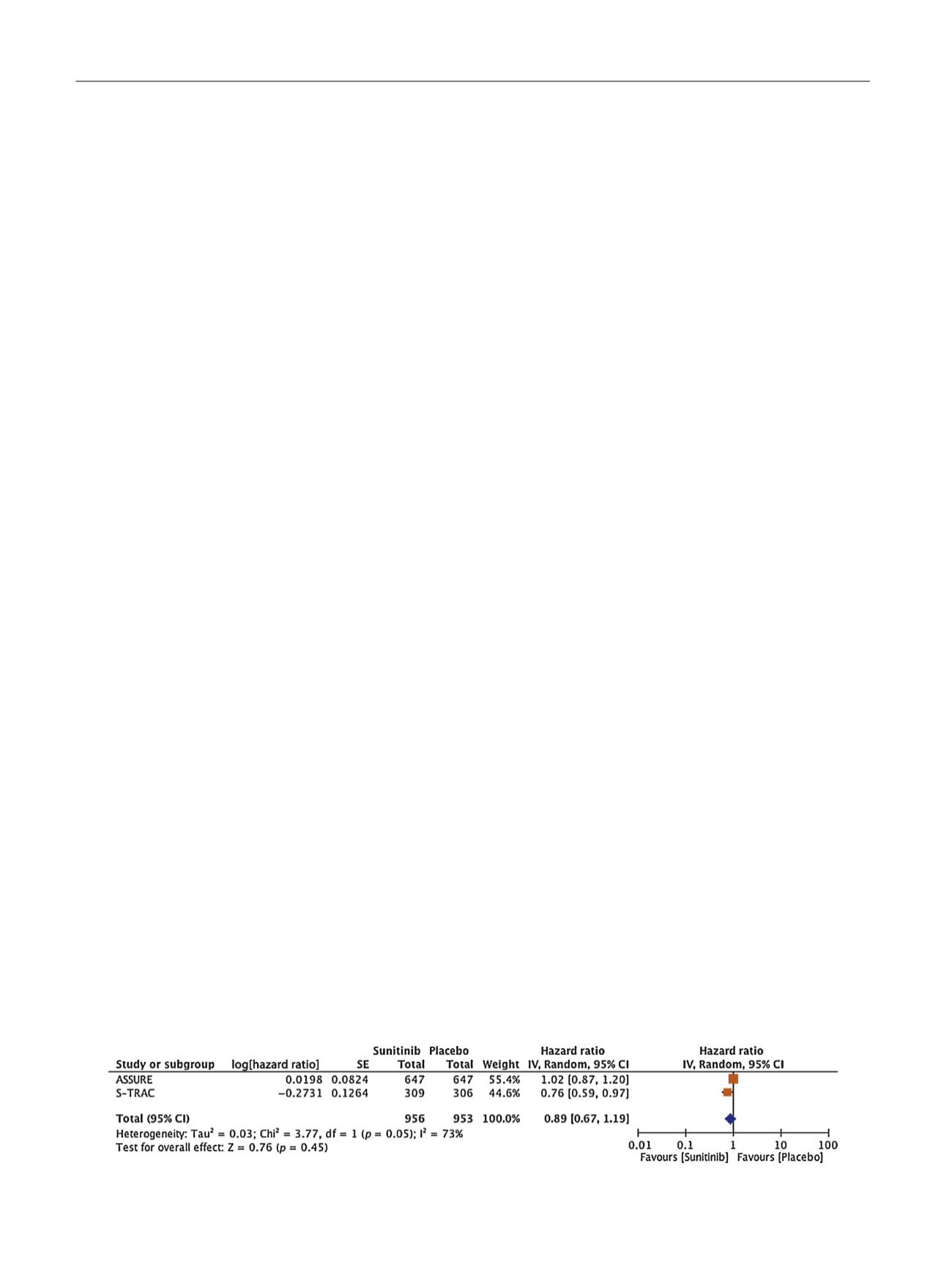

Where multiple studies exist, meta-analysis is a power-

ful tool. Again, for breast cancer and other tumour types,

meta-analysis is the driver that influences guidelines, rather

than a single study

[5,7,10]. Results from a meta-analysis of

ASSURE and STRAC trials show statistically nonsignificant

results for DFS owing to the sheer size of ASSURE

( Fig. 1;

combined HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.67–1.19). OS is immature, but

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Fig. 1 – Meta-analysis of disease-free survival (DFS) for S-TRAC and ASSURE. CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error; df = degrees of freedom.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 1 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 7 1 9 – 7 2 2

720