fourth quartile of the patients in this study (

[3_TD$DIFF]

Supplementary

Fig. 1). Below this level, the parameters identified in this

study enable further detailed risk assessment suggesting

that using clinical and demographic parameters should be

preferred to crude life expectancy prediction based on

government life tables at least in the particularly clinically

critical population of men considered suitable for radical

prostatectomy at an age of 70 yr or older.

Patients undergoing radical prostatectomy are selected

with favorable risks. Therefore, at the same numeric level of

comorbidity, age-adjusted competing mortality rates are

only approximately half as high as in unselected patients

[10] .This selection effect is particularly pronounced beyond

the 70th yr of age

[3] .Obtaining valid predictions of

competing mortality requires taking these facts into

account. All five comorbidity classifications

[5–9]compared

with the newly developed score contained the three

conditions (chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, and

other tumors) that were not associated with increased

competing mortality in our sample of elderly patients,

whereas other meaningful parameters (ASA class 3, level of

education, and current smoking) were not included (excep-

tion: current smoking in the Lee mortality index)

[7] .These

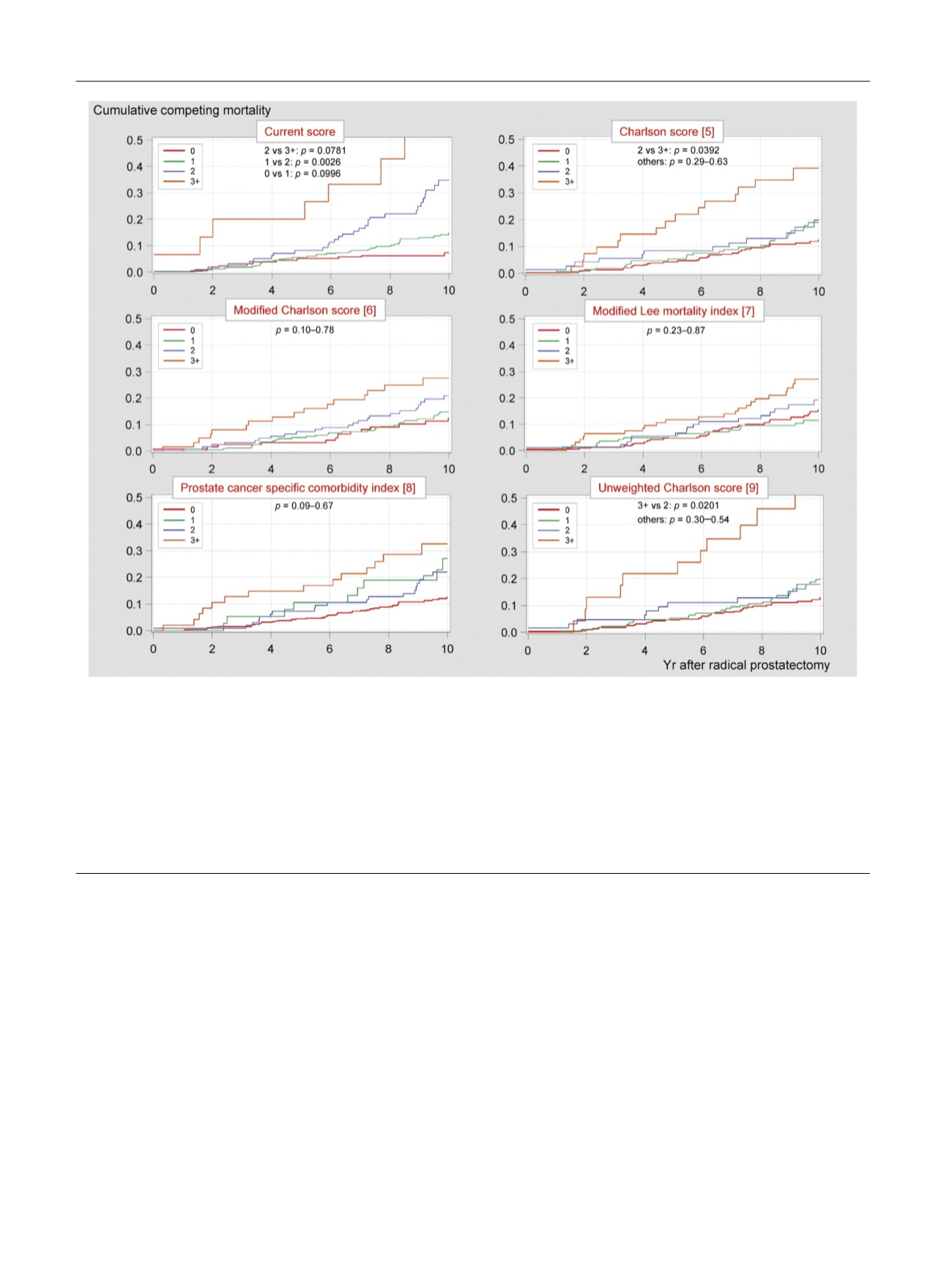

facts could explain the poor separation of the cumulative

mortality curves in the lower risk classes of the compared

comorbidity classifications

( Fig. 1; none of the cumulative

mortality curves of the three lower risk strata differed

significantly from each other in either of the compared

comorbidity measures). The identification of long-living

elderly men is of considerable importance for prostate

cancer screening and for the individualized management of

prostate cancer

[4]. The results of this study suggest that

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Fig. 1 – Cumulative competing mortality curves with Pepe Mori test

p

values and Akaike’s information criterion (lower is better) for the suggested mortality

[1_TD$DIFF]

score (upper diagram in the left column) and five other comorbidity scores using the stratification 0 versus 1 versus 2 versus 3 or more points for all

scores in our sample of 543 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy at an age of 70 yr or older. The Akaike’s information criterion was 1425 for the

current score and ranged between 1452 (unweighted Charlson score) and 1460 (modified Lee mortality index) for the comparators. The following

modifications were made with the tested scores according to the availability of data in our database: (1) modified Charlson score

[6]: data on depression,

Parkinson disease, and multiple sclerosis was not available in our database, these conditions were not considered in calculating this modified Charlson

score, (2) Lee mortality index

[7]: no subdivision between skin cancer and nonskin cancer was made; functional impairments which were not available in

our database and are unlikely of being encountered in candidates for radical prostatectomy were ignored; patients with unknown smoking status were

considered nonsmokers, (3) prostate cancer specific comorbidity index

[8]: other neurological disease, mild renal disease, arrhythmia, valve disease, and

inflammatory bowel disease were not available in our database and were not considered in calculating the index. All cases of chronic lung disease were

considered mild in our study. No subdivision between obstructive and restrictive lung disease was made

[2_TD$DIFF]

. Age-related components in the Lee mortality

index

[7]and the prostate cancer specific comorbidity index

[8]were not used in calculating these scores for comparison.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 1 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 7 1 0 – 7 1 3

712