An RCT with double blinding, few missing data, and good

compliance will have high internal validity, but if an RCT

recruits only a very select population, the external validity

(generalizability) may be low. This can happen because of

overly restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria or inclusion of

only expert clinicians in select sites

[16]. Single-center RCTs

typically have lower external validity compared to multicen-

ter RCTs that allow comparison of results between centers.

Finally, robust, adequately powered RCTs with long-term

follow-up are difficult to organize, expensive, and resource-

intensive. Thus, many RCTs focus on short-term or

surrogate outcomes, the clinical significance of which is

often uncertain. Any short-term benefits might not be

maintained over the longer time horizons that are more

relevant to patients, clinicians, and policy-makers

[17].

3.

Advantages and limitations of SRs and MAs

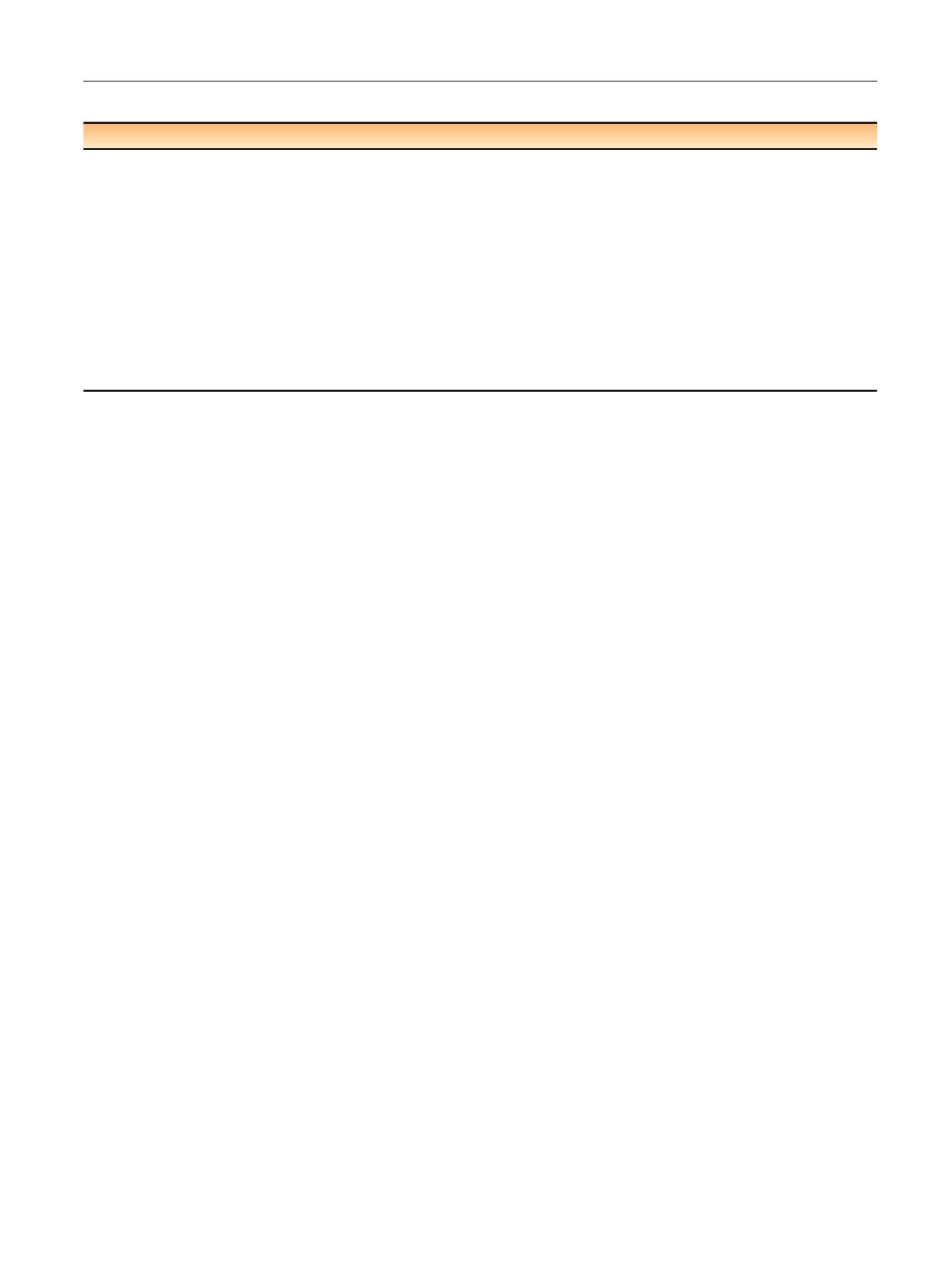

Table 2outlines the advantages and limitations of SR/MAs.

3.1.

Advantages of SR/MAs

An SR is a literature review focused on a research question

that tries to identify, appraise, select, and synthesize all

research evidence relevant to that question.

SRs are a priori defined in a participant, intervention,

comparator, outcome (PICO)–based protocol outlining the

study inclusion criteria. They are the only transparent and

replicable form of literature review that provide a rigorous

and critical qualitative appraisal of the evidence related to

an intervention. SRs explore the findings of individual

studies, draw attention to their differences, and identify

sources of bias

[18].

An MA is a statistical technique for quantitatively

combining data from two or more separate RCTs asking

the same or a similar question

[19]. They should only be

performed as part of an SR, otherwise the MA is a combined

analysis that is susceptible to study selection bias. Two

different types of MAs exist: literature-based or aggregate

data MAs, and individual patient data (IPD) MAs

[20,21].

MAs provide an overall estimate of the size of the

treatment effect, giving due weight to the size of the

individual RCTs. They are useful when individual studies are

underpowered or yield inconclusive or conflicting results,

or when an overall, more precise estimate of the size of the

treatment effect is required. MAs increase the power to

detect moderate but clinically meaningful differences in

treatment outcome and assess if the treatment effect is

similar across different studies or types of patients

[22]. They are useful in exploring the effects of an

intervention in subgroups of patients, especially in IPD

MAs

[20,21].

SRs and MAs are vital for guideline developers,

healthcare providers, patients, researchers, and policy-

makers in order to guide clinical practice, research, and

healthcare policies

[23].

3.2.

Limitations of SR/MAs

The validity of an MA depends on the quality of the SR on

which it is based. SRs and MAs have a number of potential

limitations, including poor quality of the studies included,

heterogeneity, and publication bias.

The literature summary provided in an SR and the results

of an MA are only as reliable as the quality of the studies

included. Although IPD MAs and multicenter RCTs can be

analyzed using the same statistical techniques for clustered

data, where the clusters are studies and centers, respec-

tively, there may be important clinical and methodological

heterogeneity between the studies in an MA since they are

not carried out based on a common protocol. The studies

may be heterogeneous regarding patients included, the

intervention, or the assessment of treatment outcome.

Although heterogeneity in treatment effect can be better

investigated in IPD MAs, the primary studies should be

similar enough to be combined, otherwise genuine differ-

ences in effects may be obscured

[24,25]. Since institutions

participating in a multicenter study are supposed to treat,

follow up, and assess patients according to a common

protocol, there is potentially a greater degree of standardi-

zation and higher quality data in multicenter clinical trials

compared to studies included in MAs.

If bias is present in the individual studies included in an

MA, MAs will compound these errors and produce a biased

Table 2 – Advantages and limitations of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Advantages

Limitations

Focused, well-defined clinical question with a

clear objective and explicit, predefined study

eligibility criteria

Comprehensive literature search strategy to

guarantee the identification of all potentially

eligible studies

Critical appraisal of all the included studies

that is used to guide the analysis and

conclusions

Increases the power to detect differences

between interventions

Increases the precision of the estimate of the

treatment effect

Allows the comparison of treatment effects

across different studies or subgroups of

patients, interventions and outcomes

Depends on the quality of the studies included

Susceptible to the effects of heterogeneity of the studies included

Clinical heterogeneity

Participants (eg, age, gender, disease severity and subtype, study eligibility criteria)

Interventions (eg, drug doses, duration/intensity of treatment, delivery, co-interventions, surgeon

experience)

Outcomes (eg, definition of outcome, outcomes reported, timing and method of measurements,

follow-up duration, cutoff points)

Methodological heterogeneity (eg, different study designs, reporting bias across studies)

Statistical heterogeneity

Publication bias

Time- and resource-consuming

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 1 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 8 1 1 – 8 1 9

813